Introduction

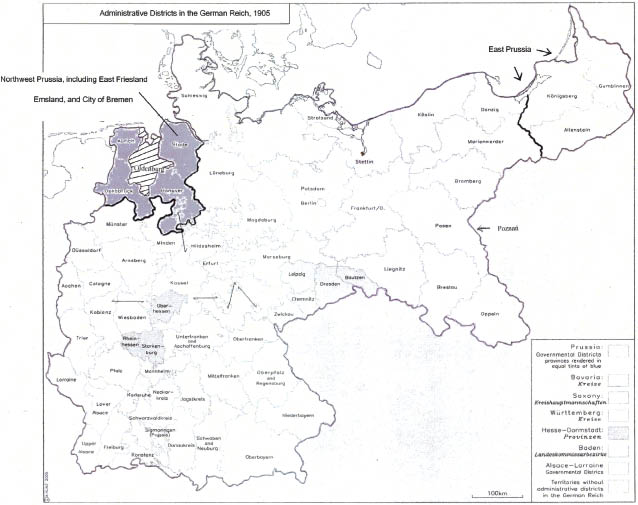

Radical German nationalist Alfred Hugenberg launched his political career in the 1890s as an official with the Royal Prussian Colonization Commission.1 Created by Bismarck in 1886, the Commission’s charge was to purchase Polish estates in the ‘racially imperiled’ eastern provinces of Posen [Poznań] and neighbouring West Prussia and replace them with German family farms. But the scheme floundered and from the backwaters of the German East, Hugenberg ascended to the Finance Ministry in Berlin, and then to the Board of Krupp Steel before joining Germany’s right-wing political elite, first as the leader of the German National People’s Party (DNVP) in the 1920s, and then as a member of Hitler’s cabinet. This brief sketch of Hugenberg’s rise neatly mirrors the current research on modern German internal colonization, or agricultural settlement, which traces its evolution in Posen and West Prussia from a fitful anti-Polish initiative to the Nazis’ ‘drive to the East’.2 Yet his early biography reveals another crucial strand in the contemporary discourse, one which highlights the transnational aspects of European internal colonization in the nineteenth century and German officials’ vigorous efforts to overhaul, or ‘modernize’, the enterprise in response to developments elsewhere. In 1891, Hugenberg, a native of the northwestern province of Hannover, published an exhaustive history of Prussia’s botched attempts to colonize the vast raised peat bogs, or high moors, on its northwestern periphery.3 Most notably, he repeatedly cited the ‘shining example’ of Dutch farm colonies to dramatize the poverty and social backwardness of Prussian moor districts in East Frisia, the Emsland and the Saterland [also Sagelterland], and in the Duchy of Oldenburg (see Figure 1). Hugenberg’s denunciations of German moor colonies, moreover, joined an outpouring of expert recriminations which had begun decades before. Thus, while bombastic claims about German ethnic and cultural superiority dominated the contemporary political discourse about colonization’s aims in the Empire’s northeastern periphery, the so-called ‘racially endangered’ East, planners invariably invoked Dutch prowess in order to pinpoint the glaring logistical deficiencies of previous efforts, reinforce the urgency of reform in existing moor colonies and provide nuts-and-bolts guidelines for future projects in all regions of the Empire.

Map of the German Empire.

Indeed, the Dutch influences on German internal colonization were far more heterogeneous and enduring than has been previously appreciated.4 This article analyzes their importance from three angles. First, internal colonization planners’ ubiquitous references to Dutch achievements and the growing worries about the wretched state of older colonies in northwest Germany profoundly shaped plans for new ones in the Imperial era, with the expectation of positive spillover effects for the entire region. Second, the catalog of earlier travails highlights the countless practical hurdles to building and nurturing new settlements, and how Germans strove to put their own stamp on Dutch models of agricultural and social improvement. Finally, despite German experts’ growing visibility in transnational debates over wasteland colonization before and after the First World War, they still invoked Dutch acumen and institutions as a spur to modern rural development, challenging scholars’ contention that the profound German influences on the Netherlands in the modern era had no analog in the other direction.5

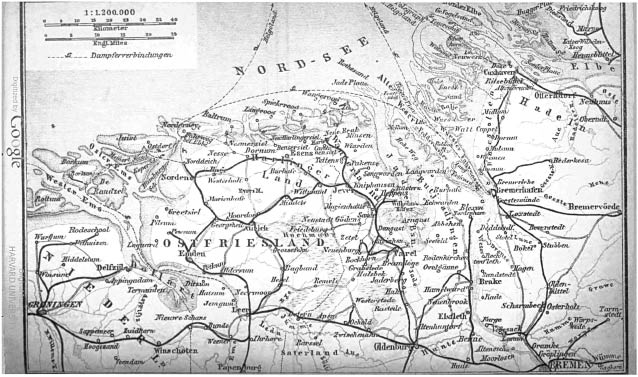

German rural experts had followed Dutch wasteland colonization activities closely since at least the eighteenth century.6 They agreed that more than any single scientific breakthrough or social insight, Dutch schemes were buoyed by a modern ethos of improvement whose keystone was planners’ emphasis on long-term rural development, bolstered by substantial state investment. Likewise, as we will see, they blasted their predecessors’ lazy reliance on cheap quick fixes, above all the practice of moor burning, which had produced ‘barbarous’ results in northwestern moor districts.7 Germans learned about Dutch projects via scholarly research, private correspondence, government reports and extended study trips, or Studienreisen. Above all, experts vaunted the fen colonies of Groningen province in northeastern Holland, which combined peat cutting, canal transport and intensive agriculture, a model subsequently applied to the hardscrabble moor landscapes of Drenthe province which extended southeast from Groningen to the German border (see Figure 2).8 After German political unification in 1871, a revitalized, state-directed programme of fen colonization sought to emulate Groningen’s example in northwest Germany. One prominent disciple of Dutch know-how was Osnabrück (Emsland) official Wilhelm Peters, whose 1875 translation of agriculturalist Tjakko Borgesius’ description of the Groningen fen colonies was widely cited.9 After 1900, rural expert Julius Frost tirelessly promoted Dutch expertise and dubbed Groningen district ‘a paradise’; indeed, as late as 1930 he was still urging colleagues to look west for ideas about modern agricultural development, including moor colonization.10 At the opposite end of the scale, historian Eugenie Berg observes that knowledge about Dutch moor reclamation and cultivation practices was exchanged through the waves of German seasonal agricultural migrants, or Hollandgänger,11 and the administrators of new German moor colonies avidly recruited Dutch applicants for their expertise in livestock-raising, openness to new agricultural methods and renowned work ethic.12 Of course, German fen colonies were never exact replicas: planners adapted some Dutch innovations and institutions quite easily, while others proved, for a variety of reasons, unworkable in the German context.13

Northwestern Germany and the northeastern Netherlands, including Groningen province (Karl Baedeker, Nordwest-Deutschland (von der Elbe und der Westgrenze Sachsens an, nebst Hamburg und der Westküste von Schleswig-Holstein) Handbuch für Reisende, 27thedition (Leipzig, 1902) 74).

Even more than the unflattering contrast between German and Dutch fen colonization, German observers used the history of fire-farming in the region to castigate their predecessors’ miscalculations and underscore the superior wisdom of Dutch policymaking. German and Dutch agronomists often noted that the practice of moor burning, or Brandkultur, had been brought to East Frisia in the 1710s by a Dutch farmer as a means of growing buckwheat.14 The ash it produced neutralized peat soils’ acidity and made them easier to work, all ‘for the price of a match’. Yet by the middle of the nineteenth century, Dutch planners typically promoted Brandkultur as a useful preparatory step for reclaiming virgin moors, or as a temporary expedient, and supported cultivators’ move to more intensive, ‘modern’ cultivation methods through education and the acquisition of livestock to supply the necessary manure.15 In contrast, under Frederick the Great’s 1765 Reclamation Edict, Brandkultur alone became the basis of several hundred colonies in East Frisia, and was avidly promoted by the Hanoverian and Oldenburg governments as a reclamation practice until the 1850s. But repeated burning exhausted the soil, which produced ever smaller yields, and after five to seven years fields needed some thirty years to recover their fertility. By the era of German unification, internal colonizers unanimously bemoaned the state’s decision to make Brandkultur the backbone of northwest Germany’s agricultural settlement endeavours, calling it short-sighted and rapacious.16 Yet, ironically, the post-unification effort to develop new cultivation techniques, spearheaded by the Prussian Agricultural Ministry, made the Empire a world leader in moor science. Called German raised bog cultivation, or Deutsche Hochmoorkultur, its promoters noted that unlike fen cultivation, Hochmoorkultur did not require the removal of the moor’s top layer and a costly network of canals, and instead relied on large quantities of artificial fertilizers and underground drainage systems. However, by the eve of the First World War, German experts agreed that the key question was not whether Hochmoorkultur or fen cultivation was the most advanced reclamation technique, but instead how to integrate the two models effectively based on local conditions.

Traversing the German-Dutch Border: Moor Colonies as Emblems of Plenty and Poverty, 1790–1866

In recent decades, studies of the parallels between German overseas imperialism and the rise of radical nationalism have shown how racial definitions of German society fueled state plans for territorial expansion between 1871 and 1945.17 More recently, historians have explored how anti-Polish racism informed efforts to ‘stamp the land with Prussian order’ in the German East.18 Building on this argument, others contend that imperial settlement planners’ frustration with the gap between aims and results laid the ideological groundwork for Nazi imperialism and its radical geospatial agenda.19 These studies help explain how ultra-nationalists used the discourse of internal colonization to inflame racial tensions on Germany’s eastern frontier and burnish their credentials as upholders of German cultural and racial superiority. But they also imply that the enterprise was insightful and well organized and that, by definition, German colonies were motors of progress in a landscape ravaged by the ‘Slavic flood’. What, then, to do with the plethora of contemporary reports about the backwardness and entrenched poverty of northwest Germany’s moor colonies? In Geography Militant, Felix Driver traces how Victorian experts constructed a domestic terra incognita in London, which then served as the foundation for a multi-layered reform programme.20 Similarly, in the first half of the nineteenth century, an expanding corps of educated Germans publicized the ‘humiliating’ backwardness of rural northwest Prussia and Oldenburg, laying the foundation for later studies that, like Hugenberg’s, offered sobering appraisals of earlier colonization disasters and proposals for improvement inspired by Dutch models.

Pastor Johann Gottfried Hoche, from the Saxon city of Halle, painted one of the earliest portraits of northwest Germany’s dismal moor dwellers.21 Traveling through East Frisia, the Saterland and the Emsland in the 1790s, Hoche likened the landscape to the ‘steppes of Siberia’, whose inhabitants were so oblivious to the wider world’s attractions that ‘they do not even aspire to them’.22 About Saterland households, Hoche confided that the men treated women ‘like slaves’, yet was astonished by women’s ‘beer visits’, where they met to sample home-brewed wares and tell jokes.23 Pioneering what became a standard itinerary for bourgeois reformers, Hoche’s final destination was Groningen province. His account was not always complimentary – he criticized the Dutch taste for luxury and the ‘frivolity’ it engendered – but like so many other observers, Hoche praised the impressive dikes, the clean villages, the wide, well-paved, and well-lit streets and ‘prettily-built’ houses.24 Decades later, in 1845, University of Kiel professor Knut Clement also recorded his impressions of Holland and Germany; he observed ruefully that Groningen farmers had ‘a drive for knowledge which our German farmers lack’.25 Of his return journey, Clement noted that Dutch cleanliness and affluence was apparent ‘until you arrive at Emmerich, on the Prussian border. At this point the villages are poorer and less attractive until you reach Mainz’.26 And eminent German agronomist Max Märcker confessed in 1875 that: ‘This author’s positive impression of the Groningen fen colonies is intensified by comparison to the barren wastes and poverty of German moor districts’.27 Märcker applauded Dutch colonists’ wealth, excellent schools, robust cattle, gleaming cleanliness and love of order; he attributed the bounty to the fact that ‘Half the workers here own their houses and farms… in no other part of Holland is there a better chance [for a colonist], through his own hands, to gain a holding and increase his net worth’.28 Decades later, in 1903, Austrian agronomist Adolf Friedrich echoed what had become a constant refrain after a study visit to the region: ‘While on the Dutch side moor colonies flank the canals for hours in unbroken rows, the smoke still rises from the [Emsland] districts of Meppen, Hümling [sic] and Arenberg, a disturbing sign of the most miserable and extensive cultivation method, moor burning, in this vast stretch [of wasteland]’.29 Like so many others, he contrasted the Netherlands, where one could observe fen colonization ‘in all of its levels of development’, with Germany’s paltry results, which were plagued by ‘piecemeal planning and one-off ventures’.30

The juxtaposition between orderly, prosperous rural Holland and the desolate, decrepit countryside of northwestern Germany was amplified by the emerging vocabulary of non-European (or Orientalist) ‘otherness’. In 1816, judge and amateur poet Godfried Bueren christened the region’s high moors ‘a dark earth-sea’ whose remote villages were like ‘an oasis in the sand oceans of Africa’.31 Another contemporary traveler compared the sand dunes of the Emsland’s Hümmling district, where the main contributing factor was unchecked moor burning, to the ‘blunt pyramids of the Tatary… One can imagine here how Cambyses’ army felt when submerged by the Egyptian sands’.32 In the 1860s, celebrated travel writer and geographer Johann Georg Kohl reinforced northwest Germany’s exoticism, calling moor dwellers ‘half-witted’ shepherds, ‘Bedouins’ and gypsies.33 At about the same time, East Frisian publicist Onno Klopp submitted that the problem was not merely environmental, but the direct result of misguided state policies. He blamed the ruinous chaos on Frederick’s 1765 Reclamation Edict, where ‘Aside from a few honorable people, good-for-nothings streamed in’.34 The problems caused by inattention to settler selection were compounded by German officials’ sanction of moor burning, which willfully exposed colonists to regular crop failures and spawned ‘hordes of urchins’. Klopp concluded, ‘The ill-conceived moor and heath colonies became like so many pus-filled boils on the land, the flourishing hothouses of crime’.35 Such pessimism fueled ever louder calls for reform in the decade before and after German unification. Still, as late as 1892, ethnographer and naturalist Bernhard Langkavel stressed the region’s dismaying otherness in his sweeping survey, Humans and their Races; in sum, he reminded readers that:

In our tour of the earth’s peoples, we still find those who resemble the remains of prehistoric races... The reader will not guess that even in Germany such early remnants persist. But it is so. Today there is a large region almost untouched by the waves of civilization, where time has stopped: I mean that region which the Romans aptly dubbed ‘the unfriendly and wrinkled brow of Germany’, namely… the high moors of the northwestern lowland.36

Dutch Models in Practice: German Internal Colonization as Rural Improvement

German efforts to tame the ‘savagery’ of its bleak northwestern periphery based on the Dutch fen model had mixed results. Between the 1790s and 1914, some two hundred fen colonies were built in northwest Germany with the intention of spearheading a broad rural improvement programme. The most enduring of these experiments, begun in the eighteenth century, were in the Duchies of Bremen and Verden, which later became the district of Stade in Hannover. By the era of German unification, the Stade district had ninety-eight moor colonies, with ca. 2876 hectares devoted to fen cultivation and ca. 1000 hectares to moor burning.37 However, the district was the first to introduce restrictions on moor burning, in 1878, and its ordinances became a model for authorities in the surrounding region.38 In 1847, state official, novelist and liberal social reformer Ludwig Starklof recounted his visits to the fen colonies of East Frisia.39 Starklof, traveling west and then north, tracked his progress from the smoky peat sod huts or, ‘stench-ridden pig sties’, of his home state of Oldenburg to the comparatively well-to-do East Frisian colonies of Rhauderfehn and Nordgeorgsfehn, where ‘Dutch life and practices prevail… Yes, here is a completely different existence in the moors [than in Oldenburg]’.40 He mused dispiritedly, ‘How is it possible that in such a short distance there are such major differences?... One factor is proximity to the Dutch border. Everything praiseworthy here has been transplanted from Holland. But why does it end so suddenly – as abruptly as if sliced by a knife?’41 At the same time, Starklof found fault with the colonists’ cottages at nearby Südgeorgsfehn, which were built too far from the canal, calling them ‘Irish hellholes [Jammerhöhlen Irlands]’.42

The Bremen-Verden and East Frisian fen colonies often were overshadowed in contemporary debates by the example of Papenburg in the Emsland, founded in the 1630s and the region’s most prosperous city by the middle of the next century. Hugenberg, in his 1891 study, praised Papenburg as the ‘highlight [Glanzpunkt] of moor colonization on the German side’.43 But he also stressed that in recent decades, a rising number of colonists had joined the poor rolls due to the slowdown in ship traffic and the increased reliance on moor burning.44 Hugenberg also could not resist citing an East Frisian official who in 1789, at the height of the colony’s boom, still compared it unfavourably to the Dutch precedent: ‘Overall in Papenburg one misses the order, cleanliness and pleasantness … which charms every traveler to Pekela, Wildervang, Veendam, etc.’45 Emil Stumpfe’s massive 1903 study of German moor colonization was much harsher: ‘If one wanted to compare our moor colonies with those of Holland… it would be even worse than the contrast between the most impoverished Kaschubian village [in the East] and the most flourishing one in the Magdeburger Börde [Sachsen Anhalt]!’46 He elaborated ‘The mistakes East Frisian fen colonization has made and still makes in comparison to the Dutch, and which, if they do not stifle the enterprise altogether at the very least sorely hinder its progress, are legion’.47 Stumpfe’s catalog of errors encompassed multiple arenas: the technical (‘for example, terrible canals’), financial (‘narrow-minded penny pinching’), administrative (‘lack of an overall plan’, ‘inefficient bureaucracy’) and socio-economic (‘plots too small’); he groused: ‘It is no surprise that German fen colonies are a faint replica of those in Holland’.48 The newer Oldenburg fen colonies, built at the end of the nineteenth century, fared somewhat better in Stumpfe’s assessment, but here, too, he lamented: ‘It is not a rosy picture. In reality, the best Oldenburg moor colony… cannot be compared remotely to the Dutch’.49 And, in the final pages, the author enjoined, ‘Here, I can only repeat: let us learn whatever we still can, especially from our great examples and teachers, the Dutch. Then success will be assured’.50

The sluggish pace of canal construction in northwest Germany, together with the weakening market for peat as a fuel source and the corresponding rise in demand for coal, persuaded many moor experts that the large-scale adoption of fen colonization in the Empire was unrealistic. Indeed, as Eugenie Berg notes, the increased use of moor burning in the Bremen-Verden fen colonies was due to the slumping demand for peat during the last quarter of the nineteenth century.51 At the same time, it was the persistence of ‘primitive’ Brandkultur at older moor colonies and, as we have seen, the growing public outcry over its cascading environmental, economic, social and moral threats, which galvanized German agronomists’ search for new moor reclamation methods.52 In 1876, responding to intense pressure from the Bremen-based Northwest Society against Moor Burning [Nordwest Verein gegen das Moorbrennen], the Prussian Agricultural Ministry established the Central Moor Commission, hereafter CMC, in Berlin.53 The new sub-committee’s job was to facilitate the development of viable alternatives to moor burning as a basis for new colonies and, secondarily, to ascertain whether the cumbersome removal of the top layer of peat prior to cultivation, as dictated by the fen model, could be avoided with the addition of artificial fertilizers and soil amendments. A year later, the CMC selected Bremen to house the Empire’s first Moor Research Station, led by agricultural chemist Dr. Moritz Fleischer. Fleischer and his team made slow progress, but after more than a decade of exhaustive laboratory and field research, the first settlers arrived at the Marcardsmoor colony in East Frisia. Designed to showcase DeutscheHochmoorkultur, the Marcardsmoor model was adopted at new colonies in nearby Wiesmoor, at Provinzialmoor in the Emsland and at Kehdinger Moor in Stade district.

By the turn of the century, the German ‘scientific’ colonies were widely admired in international agricultural circles and celebrated as the launching pad for future projects. Kaiser Wilhelm himself attended the 1899 annual meeting of the Central Moor Commission about the potential of Hochmoorkultur to ‘unlock’ the Empire’s high moors through reclamation and settlement.54 Experts celebrated large increases in Marcardsmoor colonists’ net worth and livestock holdings and cheered that, ‘All those who have anything to do with the project give it the highest marks’.55 Ever the contrarian, Stumpfe nonetheless cautioned that the new method, which he dubbed the ‘Marcardsmoor-System’, was still in need of adjustment.56 And as late as 1914, eminent internal colonization booster Conrad von Wangemheim blustered defensively that despite the ‘natural’ missteps which had plagued the Marcardsmoor and Provinzialmoor colonies, ‘Today we stand at the forefront of moor science, and even under our more challenging conditions, under no circumstances should we shy away from comparisons with Holland’.57

Quick as they were to trumpet Hochmoorkultur as the product of German expertise and its potential to transform the enterprise of internal colonization, rural experts also grasped that a simple substitution of Hochmoorkultur for fen cultivation or, for that matter, Brandkultur, was impractical.58 By the 1890s, the debate had shifted away from either/or to the logistics of how to combine the two ‘advanced’ models based on meticulous evaluations of local conditions. This hybridity clearly informed the planning of the new scientific colonies, where canal access was deemed key to their viability: in the case of Provinzialmoor, it was the Südnord-Kanal and at Marcardsmoor, the Ems-Jade-Kanal. Thus in 1888, Prussian Agricultural Minister Hugo Thiel observed about the Marcardsmoor plan that ‘We can assume that colonists initially will practice Hochmoorkultur, but it is also anticipated that some may eventually replace it with fen cultivation’.59 Prussian Agricultural Minister von Hammerstein’s progress report expressed the same sentiment in 1890, when he warned that in light of the fact that Hochmoorkultur was still in its experimental phase, the colony’s lay-out must prioritize colonists’ easy access to the Ems-Jade-Kanal.60 Moreover, agricultural experts’ emphasis on German-Dutch hybridity as the key to success did not recede, and instead became conventional wisdom: a 1908 report by the Association for the Advancement of Moor Cultivation in the German Empire averred that ‘the two cultivation systems are not mutually exclusive… Hochmoorkultur should be understood as a highly desirable complement of the fen method.’61 J. P. Zanen put an even finer point on this way of thinking in his 1906 study, The Current State of Moor Cultivation and Colonization in the Empire, when he contended that it would be more accurate to speak of ‘Dutch-German’ Hochmoorkultur.62 By this time, German agronomists also acknowledged that with respect to the use of potash salts, a key ingredient for the transformation of peat soils into productive arable, the Netherlands had surpassed Germany as the world leader: in 1906, Dutch farmers used 959 kilograms of potash per square km, while in Germany, which held second place, the figure was 651.3 kilos per square km.63 Indeed, as one quipped, ‘regarding the use of artificial fertilizers, Holland is… “the country of unlimited possibilities” ’.64 Thus despite the steady progress of German moor colonization in the decades before the First World War, planners still frequently expressed the sense that whatever gains were made, the Dutch always remained one or two steps ahead. For example, the 1909 Meyer’s Encyclopedia entry for ‘moor colonies’ commented that ‘If the imitation of the Dutch model on the German side of the border… have not even faintly…achieved the positive boom of the Dutch colonies, then this is basically due to the flaws of weak investment, the lack of a unified vision … (and) that priority was given to shipping interests rather than to the technical aspects of agriculture favourable to cultivators.’65

Even as German moor scientists slogged through the knotty technical obstacles to the establishment of prosperous moor colonies, reformers also searched for models of landholding which would allow hard-working colonist families of modest means to enhance their chances of eventual farm ownership. The debates over how to anchor ‘little people’ to the land had begun after 1848, but they assumed tremendous urgency during the far-reaching economic and social upheavals unleashed by the Great Depression in 1873. In particular, Germany’s premier social reform organization, the Verein für Sozialpolitik, determined that the Prussian government’s 1850 abolishment of the institution of hereditary leaseholds, or Erbpacht, had inadvertently amplified the crisis of rural flight.66 Regardless of their political sympathies, German rural policymakers unanimously emphasized the need to construct a sturdy ‘social ladder’ where diligent agricultural hired hands and small leaseholders could become self-sustaining, or full-time, family farmers.67 Here, too, like agronomist Max Märcker cited above, numerous commentators noted that the Groningen institution of the ‘beklemregt’ or ‘vaste beklemming’, a form of inherited leasehold, was a central pillar of the district’s success.68 The beklemregt was the main subject of an 1879 Central Moor Commission meeting; the CMC’s ringing endorsement of the model was echoed by the Verein für Sozialpolitik, which described it as ‘a type of inherited lease which evolves gradually from a limited term contract [Zeitpacht]… which forbids subdivision by tenants or their eviction without notice… and which through all the political and legal shifts in Holland has managed to establish and sustain a prosperous farming class’.69 In the same year, Bonn agricultural expert Erwin Nasse commented, ‘All Dutch economists agree on the advantages of the beklemregt, all attribute the province’s unusually strong agricultural development to the institution’.70 Almost four decades later, in 1913, Dutch economist Conraad Verrijn Stuart proudly informed his audience of German policymakers that ‘almost three quarters of the farmers [here in Groningen] own their land’.71 Rebutting criticism that the 1890 and 1891 German Hereditary Leaseholds Acts [Rentengutsgesetze] were unnecessarily restrictive, the laws’ defenders pointed to its embrace in ‘free-thinking’, ‘liberal’ and ‘eminently practical’ Holland.72

Dutch Colonists as Embodiments of Improvement

In light of the discussion so far, it is hardly surprising that German planners eagerly sought Dutch applicants for the new scientific colonies. The idea was not new. An early example from the modern era was Frederick William of Prussia, the ‘Great Elector’, who in the seventeenth century had invited farmers from the Netherlands to settle the reclaimed marshes of Brandenburg, perhaps under the influence of his Dutch wife, Kurfürstin Luise.73 In northwest Germany, Dutch colonists were crucial in the revitalization of North Frisia, especially the island of Nordstrand, after severe floods in 1634, 1718, and 1815. In 1884, rural expert Georg Hanssen explained that ‘The colonization of Nordstrand by the Dutch gave the island an advantage compared to others in Schleswig province… [besides their technical expertise] even more important was their knowledge of agriculture and livestock-raising, which provided a model’ for the surrounding region.74 The early twentieth century saw renewed interest in the idea. Besides informing German policymakers about the benefits of the beklemregt, Verrijn Stuart described how Groningen farmers continued to advance moor cultivation in Nordstrand and nearby Dünenbroek.75 Another typical example was Stumpfe’s contention that the Oldenburg colonies’ ‘best hope for a new epoch’ were the present efforts to recruit Dutch settlers; his colleague Otto Gramberg also praised the effort to lure Dutch fen colonist families and to ‘plant them among our colonists as model cultivators, who in most cases are unaware of the practical tricks and tools [Kniffe und Griffe]. Naturally, success will only be gradual’.76 A decade later, Franz Böcker, the head of the Oldenburg Agricultural Chamber [Landwirtschaftskammer], reported that Dutch colonists were fueling demand for plots in the region because land prices in the Netherlands had soared and the ratio between agricultural wages and food prices in Germany was more advantageous.77 Böcker attributed the progress of reclamation and the expansion of livestock holding there to the recent Dutch influx, who ‘have inspired the Oldenburgers in numerous ways and at the same time helped shield them from fruitless experiments. That in turn has prompted many [German] families of workers to become leaseholders and remain on the land who otherwise would have been lost to industry or overseas’.78 Likewise, in a discussion of new colonists’ most desirable attributes, Wilhelm Rothert contended that friction between scientists and colonists was sometimes productive; to illustrate this, he cited the example of Dutch colonist de Graaf in Provinzialmoor, who had ‘blatantly defied the authorities by expanding his meadows and pastures in order to build his livestock holdings…the experiment was a huge success and transformed the practice of Hochmoorkultur… greatly increasing its profitability’.79

The story of how the de Graafs, father and son, moved with their families from the Provinzialmoor colony in the Emsland to Marcardsmoor in the autumn of 1901 highlights just how desirable Dutch applicants were. In late July of that year, B. de Graaf and his son G. de Graaf visited Marcardsmoor to get the lay of the land, and informed the assistant administrator [Moorvogt] that their interest in leaving Provinzialmoor for plots at Marcardsmoor was motivated by their desire for a Protestant community rather than a predominantly Catholic one.80 The administrator privately expressed his delight to the regional commission which oversaw internal colonization matters, the Hannover General Commission [Generalkommission Hannover], and asked for permission to recruit them; tellingly, he also worried that his Provinzialmoor colleagues would be sorely vexed, but this did not hinder the recruitment effort. The ensuing six weeks of negotiations with the de Graafs reveal that so-called ‘model colonists’ could and did request major alterations to the contract, and the de Graafs’ keen awareness of their leverage. Indeed, at several apparent sticking points, Marcardsmoor’s overseer cautioned his superiors that B. de Graaf was a ‘very intelligent man’ and more than once pleaded with them to give ground on his list of demands.81 These included the waiving of the 300 Mark cash deposit and a better price for artificial fertilizers. The local authorities eventually persuaded Hannover officials that the Dutch applicants were a good investment, since the plots they sought had been left in poor condition by the previous leaseholders and they had extensive knowledge of livestock-raising. Summing up his case for the de Graafs, the Marcardsmoor overseer conceded that ‘while in principle internal colonization should be for [German] citizens, exceptions ought to be made if suitable domestic applications are lacking and they are willing to settle permanently’.82 Several years later, in the summer of 1905, the elder de Graaf died and the Marcardsmoor plot was taken over by his widow and another grown son; B. de Graaf departed for Holland some time in 1904, with the reason given that ‘he never felt quite at home’.83

Conclusion: The Netherlands and Narratives of German Internal Colonization

The recent emergence of internal colonization as a central theme in the history of modern Germany is clearly indebted to the explosion of scholarship on European colonialism and the racist colonial imagination. Viewed from this perspective, internal colonization in the German Empire was the domestic counterpoint to Kaiser Wilhelm’s jingoistic jostling for an overseas ‘place in the sun’, and provides a new lens for examining the mutually reinforcing racial and spatial priorities of ultra-nationalist politicians in the Empire. Accordingly, the analytical focus is placed on internal colonization as a discursive weapon for asserting and cementing German racial superiority vis-a-vis Polish ‘Unkultur’ on the Empire’s eastern periphery. Moreover, scholars assert that prewar internal colonization’s perceived failure to remedy the racial imbalance helps explain the Nazis’ outsize fantasies of Eastern conquest after 1933. Yet what has been overlooked in these studies is how earlier wasteland colonization endeavours fueled surging anxieties about German rural backwardness in the nineteenth century and how profoundly these cautionary tales influenced post-unification endeavours. And in their diagnosis of German deficiencies in this arena, as well as their proposals for improvement, social observers, scientists, engineers and state officials overwhelmingly drew inspiration from the Dutch example. This took various forms, ranging from deep admiration to frustration with pale German imitations to defiant declarations that the Empire was at long last catching up to their western neighbour.

Indeed, references to Dutch mastery and German backwardness run like a red thread through the wide body of contemporary literature on internal colonization in Germany both before and after national unification. The fact that these ubiquitous comparisons have been ignored signals how much historians still have to learn about internal colonization as a material, everyday enterprise, especially how planners and colonists worked to translate blunders into practical lessons for future wasteland reclamation and colonization projects. In a broader sense, the history of Dutch influences on the building of new agricultural colonies in the Empire revises the longstanding narrative that Germany’s rise after 1871 was powered by unwavering convictions about its technical and cultural superiority, and similarly conventional assumptions about Dutch ‘decline’ in the modern era. The evolution of new projects like Marcardsmoor highlighted the ways that moor reclamation and colonization were in fact the product of trans-regional collaborations, even as they were celebrated as exhibitions of national triumph. Moreover, for ultra-conservatives like Hugenberg, Stumpfe and von Wangenheim, the relevance of the Dutch example extended beyond Germany’s northwest periphery: as Hugenberg emphasized, the insights gained there accumulated value as they rippled eastward.84